Sleep For Surgeons

But why is sleep so important, and how can we optimise it?

It’s recommended that adults get between 7-9 hours of sleep.[2] Individual requirements vary, but it is rare to need less... rarer than being struck by lightning, according to Matthew Walker.[3] Yet, a third of us suffer from ‘insufficient sleep syndrome’, a ‘voluntary’ state of chronically reduced sleep to accommodate lifestyle or work demands; and insufficient sleep has been declared a global public health issue because of its impact on our health.[4,5]

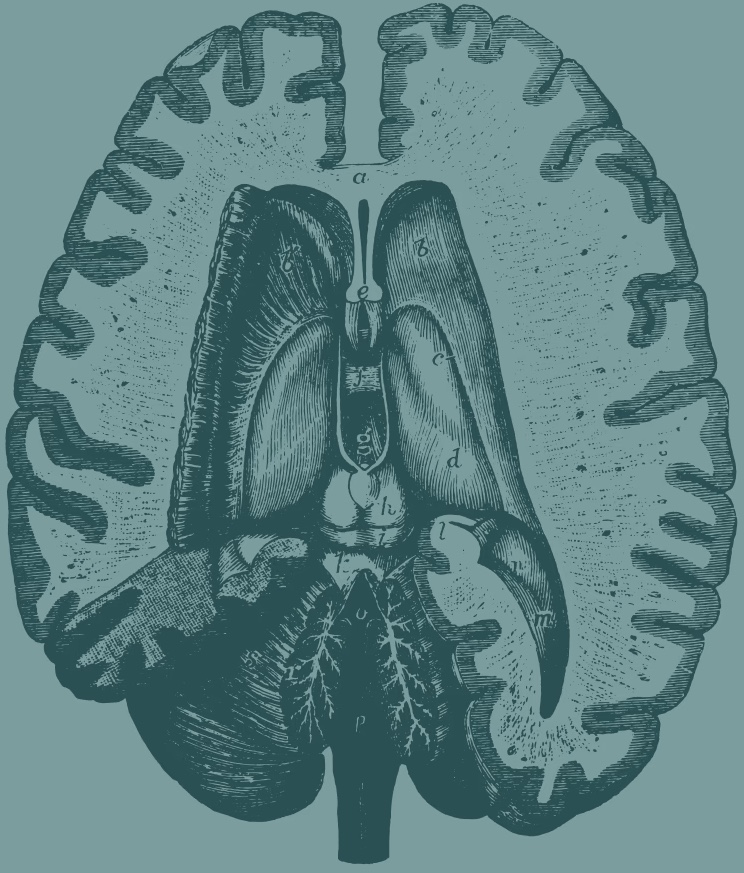

We sleep in 90 minutes sleep cycles, with more restorative deep sleep at the beginning of the night and more creative, emotionally regulating REM (or ‘dream’) sleep in the second half of the night. We need to sleep deeply enough to get enough deep sleep, and for long enough to get enough REM sleep (see figure, above [6]). You can read more about sleep here, or hear more, here.

I’ve divided this topic into: Going to sleep, staying asleep, and waking up refreshed.

[2] The National Sleep Foundation, accessed Feb 2025

[3] Walker M. (2018). Why we sleep. Penguin Books.

[4] Chattu et al. Sleep Sci. 2018;11(2):56-64

[5] Sleep: A neglected public health issue. Lancet Diab & Endocrin. 2024;12(6):P365

[6] Chasser C, Cooper L. Sleep for Surgeons. Bulletin RCS (Engl.);2025;107(2)

Going to sleep

Sleep is a vulnerable state. We will only let ourselves sleep deeply if we feel that it is safe, and that it is the right time, to do so.

Read more →Staying asleep

It may not be falling asleep that’s the problem, but staying asleep. There are lots of reasons why we wake up in the night and the good news is there’s lots that we can do about it.

Read more →Waking refreshed

You're getting to sleep, and staying asleep but never waking refreshed. What can you do about it?

Read more →Live your day in a way that supports sleep

We are often guilty of thinking of sleep in isolation, but how we live our day sets us up for how we sleep.

Read more →Resource Lucky Dip

Why We Sleep (book)

Featured in: Rest/Nap, Understanding Sleep, Audiobooks

Top five regrets of the dying (book, audiobook)

Featured in: Audiobooks, Books, Connection

Insight timer

Featured in: Meditation, Sleep, Alternative To Looking At A Screen

Whoop

Featured in: Trackers (Body Worn), Understanding Sleep, Sleep

Simba cooling pillow

Haven't found what you're looking for?

This is intended to be a place where busy healthcare professionals can come to find resources to support their fulfilment, productivity, health and performance.

Is there anything missing that you’re looking for? Or anything that has been useful for you that you would like to share? Any niche requests for recommendations? I would love to hear from you.